Who are Palestinian Refugees?

According to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA)—developed as temporary relief for Palestinian refugees through the provision of basic health care, education and employment—Palestinian refugees are persons whose normal place of residence was Palestine between June 1946 and May 1948, and who lost their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbours during this period. UNRWA also includes descendants of people who became refugees in 1948.

In 1949, 156,000 Palestinian Arabs remained in Israel and would become Israeli citizens; 32,000 of them were Palestinian internal refugees who were not allowed to return to their lands. The rest of the Palestinian refugees, those who found themselves outside the new state of Israel in 1949, were not allowed to return to their homes, and were granted no compensation from the newly formed state.

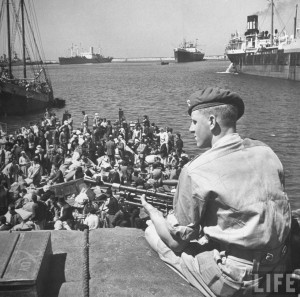

By 1949, more than 500 Palestinian towns and villages had been depopulated and destroyed and approximately 711,000 Palestinian refugees, according to the UN, were dispossessed. By 1953, there were 870,000 registered refugees, more than 34 percent of them in refugee camps in Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt. Bureaucratic complications prevented many refugees from registering with UNRWA, which suggests that the actual number of refugees was higher than the number of those registered (1).

Origins of the Palestinian Refugee Crisis

The Palestinian refugee crisis is a direct and inevitable consequence of the establishment of a Jewish-dominated state in historic Palestine. Following the United Nations proposal to partition Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states —a proposal that did not involve consultation with or approval by the native Palestinian population, and that gave 55 percent of the land to the Jews, who constituted a third of the population in historic Palestine and owned 6 percent of the land—Jewish militias began forcibly removing Palestinians from their homes and villages. The proposed Jewish state would have contained 498,000 Jews and 407,000 Arabs (not including 90,000 nomadic Bedouins) (2). Consequently, between 1947 and 1949 over 700,000 Palestinians were forcibly expelled or had to flee their homes and villages for fear of violence from Jewish militias.

This campaign of violently expelling Palestinians from their homes and villages is referred to as Plan Dalet and was spearheaded by Israel’s first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, and his “consultancy” of roughly a dozen military and security figures. The goal was to remove the native Palestinian presence from the land in order to create their desired Jewish majority in a newly declared state (3). As a result, up to 90 percent of the Palestinian population was expelled, fleeing to the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, and the surrounding Arab countries of Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt and Iraq. The implementation of Plan Dalet began before Arab armies attacked Israel in the 1948 war.

Although the 1948 war ended with a set of armistice agreements in 1949, incidents of forced displacement of the local population took place up until at least the late 1950s (4). Today, the total Palestinian refugee population numbers more than six million people. They are barred from returning to their homes or properties by the state of Israel, despite their right to do so under international law.

Legal Basis of the Right of Return for Palestinian Refugees

The legal basis for the Palestinian right of return is firmly entrenched in international law. According to Susan Akram of Boston University Law School, founder of the Asylum and Human Rights Clinic at Greater Boston Legal Services, the right of return is “found in the major treaties and rules protecting individuals and groups in times of armed conflict under humanitarian law and the laws of war; it is found in treaties and principles governing issues of nationality and state succession; and it is found in the core human rights conventions governing state obligations in both war and peacetime, particularly in refugee provisions (5).”

Some of these relevant areas of international law pertaining to the Palestinian right of return are given below.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR):

The UDHR was adopted by the UN in December 1948, applying to all member states, including Israel. Article 13(b) of the UDHR states: “Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.” Palestinian refugees are entitled to this universal right, as are all other refugees.

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR):

The ICCPR was signed by Israel on October 3, 1991. Article 12(d) of the ICCPR states: “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of the right to enter his own country.” In addition to the right of return being enshrined in customary international law, Israel is obligated to abide by its tenets by virtue of having ratified this covenant.

United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Resolution 194:

UNGA Resolution 194 was passed a day after the UDHR, to affirm the existing norm within customary international law enabling refugees to exercise the right to return to their homes and properties. Paragraph 11(a) of the resolution states that the UN

Resolves that the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible.

While General Assembly resolutions are non-binding under international law, UNGA Resolution 194’s purpose was to affirm existing rules of international law, rather than to create new ones. Count Folke Bernadotte, who was the UN Special Rapporteur to Palestine, called on the General Assembly to affirm and maintain the rights of displaced people, which are legally binding under customary international law. Furthermore, the 1907 Hague Regulations called for reparations in the form of restitution or compensation to land and property owners for the destruction and pillaging of property, which occurred in the absence of military necessity. Israel was therefore held liable for reparations for these crimes before UNGA Resolution 194 was passed.

Ultimately, the UN’s acceptance of Israel’s declaration of statehood was conditional on Israel’s acceptance of the Palestinian right of return. UNGA Resolution 194 strongly reflects the will of the international community, as it has been reaffirmed by the UN more than 135 times.

UNGA Resolution 181 (II) (Partition Plan):

Despite the fact that UNGA Resolution 181(II)—the proposal to partition Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state—was unjust to the Palestinians, the resolution called on all parties to protect the minority rights in each proposed state. The resolution explicitly states that

no expropriation of land owned by an Arab in the Jewish State (by a Jew in the Arab State) shall be allowed except for public purposes. In all cases of expropriation full compensation as fixed by the Supreme Court shall be paid previous to dispossession.

Again, while General Assembly resolutions are non-binding under international law (meaning the partition plan that helped to create Israel was a non-binding resolution), the Jewish leadership accepted this resolution and based Israel’s Declaration of Independence “on the strength of the resolution of the United Nations General Assembly [Resolution 181].” Therefore, according to the UN, Israel is bound by the resolution’s provisions, including the provision that explicitly protects minority rights and property interests (6).

United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 46:

Adopted on April 17, 1948, slightly less than a month before Israel’s Declaration of Independence, the UNSC passed a resolution safeguarding the rights of the inhabitants of Palestine. UNSC Resolution 46 called on all persons and organizations in Palestine to

refrain, pending further consideration of the future government of Palestine by the General Assembly, from any political activity which might prejudice the rights, claims, or position of either community.

Meanwhile, the Haganah (which later became the Israeli Defense Forces) had already begun systematically destroying Palestinian villages and expelling the population. UNSC resolutions are legally binding under international law, which makes Israel liable for restitution or compensation for those Palestinians who fled.

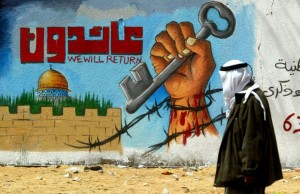

Implementation of the Right of Return of Palestinian Refugees

It is not only necessary for Israel to acknowledge the Palestinian refugees’ right to return to their homes, but every attempt should be made to implement this right for “refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours (UNGAR 194).” Those refugees whose homes no longer exist, or who choose not to exercise this right, are entitled to adequate compensation. In order for peace, justice and reconciliation to prevail, Israel needs to accept responsibility for its violent dispossession of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, and its refusal to allow them to return to their homes and properties. This is a Palestinian right, which cannot be extinguished as part of a peace agreement with Israel. This right is an individual right, in addition to a collective one.

Implementing this right will not require the displacement of Israel’s existing population. Palestinian geographer Salman Abu-Sitta has conducted studies that show that the areas from which the majority of Palestinian refugees originated are inhabited today by only 1.5 percent of Israel’s population, and that the large majority of former Palestinian towns remain vacant. According to Abu-Sitta, “well over 90% of the refugees could return to empty sites. Of the small number of affected village sites, 75% are located on land totally owned by Arabs and 25% on Palestinian land in which Jews have a share. Only 27% of the villages affected by new Israeli construction have a present population of more than 10,000. The rest are much smaller (7).”

The right of refugees to return to their homes and properties would need to be balanced with the second-occupancy rights of Jewish Israelis, who also have a connection to the land and should not be displaced as a result of a return of refugees (8). BADIL and Zochrot have begun thinking about this issue, and propose that in certain cases mediation and arbitration will be used to determine second occupancy rights (9). As Ibish and Abunimah note: “Once Israel accepts the right of return, Palestinians and Israelis will then have to negotiate modalities for the orderly administration of a return program. This could include limits on the number of refugees returning each year, although not a cap on the total who would have the right to return, among many other administrative options (10).” Many Palestinian refugees may decide not to return to their homes and properties, or to return only to visit but not to live. In any event, this is each individual’s inalienable right to decide.

Endnotes:

(1) Morris, Benny, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 2004.

(2) United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP), Report to the General Assembly, vol. 1, p. 54.

(3) Khalidi, Walid, “Plan Dalet: master plan for the conquest of Palestine”, J. Palestine Studies 18 (1), 1988, p. 4-33; Pappe, Ilan, The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, OneWorld, Oxford: 2007.

(4) Senechal, Thierry and Hilal, Leila, “The Value of 1948 Palestinian Refugee Material Damages: An Estimate Based on International Standards” in Compensation to Palestinian Refugees and the Search for Palestinian-Israeli Peace, Ed. Rex Brynen and Roula El-Rifai, Pluto Press, London: 2013, p. 132.

(5) LeVine, Mark, “Why Palestinians have a right to return home”, Al Jazeera, September 23, 2011, accessed from http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2011/09/2011922135540203743.html on July 23, 2013.

(6) United Nations Committe on the Exercise of the Inalienable Rights of the Palestinian People (CEIRPP), The Right of the Return of the Palestinian People, UN doc. St/Sg/SER.F/2, 1 November 1978 at Chpater IV.

(7) Abu Sitta, Salman, “The Implementation of the Right of Return”, Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture, vol. 15 (4), August, 2009.

(8) Kagan, Michael, “Do Israeli Rights conflict with the Palestinian Right of Return? Identifying the possible legal arguments”, BADIL, Working Paper No. 10, August 2005.

(9) Jamjoum, Hazem (Ed), “Transfer of Population… Return of the People”, Al Majdal, BADIL, No. 49 (Spring-Summer 2012).

(10) Ibish, Hussein, and Abunimah, Ali, “Point: The Palestinians’ Right of Return.” Human Rights Brief 8, no. 2 (2001): 4, 6-7.